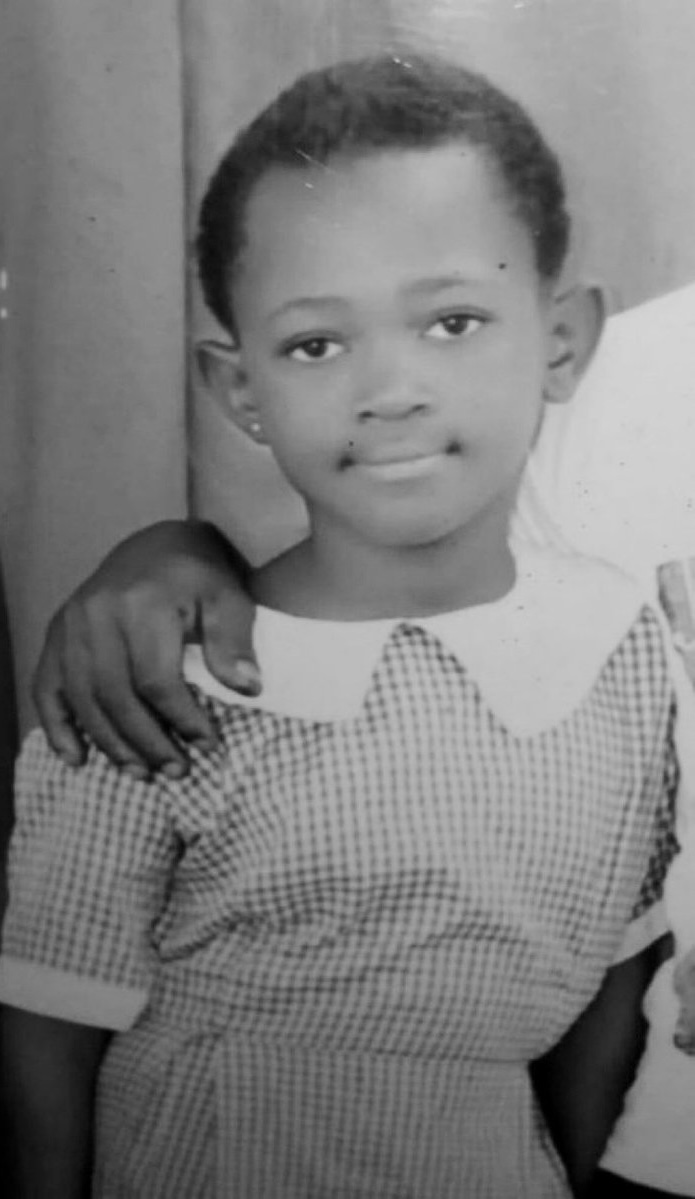

To be a girl or a woman in Nigeria is to be a student in a lifelong school of survival. It is to learn, from an age you cannot yet comprehend, that your body is a battleground, your safety a negotiation, and your freedom a privilege, not a right. On this International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, we are chronicling a reality lived in a state of perpetual siege, a weary existence defined by the violence we, women, are forced to endure.

Nigeria’s Schools Are A Hunting Ground

It begins in the classroom, a place meant to be a sanctuary of learning and aspiration. Instead, it has become a hunting ground. We thought that the chilling abduction of 276 schoolgirls from Chibok in April 2014 was an anomaly, if only we knew it was the horrifying prologue to a continuous national tragedy. A decade later, with 82 of the Chibok girls still in captivity or unaccounted for, their stolen futures serve as a constant, gaping wound. But the wound has never been allowed to heal. It is torn open again and again: in 2018, with the 110 girls stolen from Dapchi; in November 2025, when armed men murder a teacher and seize 25 students from a girls’ school in Kebbi; and just days later, when over 300 children, mostly girls, and staff are abducted from a Catholic school in Niger State.

These are not isolated incidents. Amnesty International has documented at least 17 cases of mass abductions since Chibok, with an estimated 17,000 children, mostly girls, seized, dragged into the bush, and subjected to unimaginable abuse. Nigerian citizens are the currency in a brutal transaction of terror and ransom, a fact underscored by the National Bureau of Statistics, which revealed that a staggering 2.2 trillion naira was paid in ransoms between May 2023 and April 2024. Abductions have become a thriving, blood-soaked industry, flourishing in the vacuum of political will.

Nigeria’s Society Is Riddled With Sexual Predators

Beyond the headlines of mass abductions lies the intimate, suffocating war waged against women in their own homes and communities. The names of the dead are a litany of our collective grief. We cry for justice for Ochanya Ogbanje, a child raped to death by her own uncle and cousin. We demand justice for Austa, whose life was stolen by her boyfriend, Benjamin Best. And as we fight for them, our hearts break for a two-year-old girl, violated by her teacher just days after she first stepped into a school. There is barely ever time to pause our grief. The National Human Rights Commission, in its October 2025 Human Rights Situation Dashboard, recorded 7,047 cases of domestic violence, 412 cases of sexual violence, and 19 cases of rape across the country. Statistics that are grossly underestimated due to the lack of reporting in gender based violence cases.

This pervasive rape culture has become so deeply embedded that it now masquerades as state-sponsored charity. In 2024, the Speaker of the Niger State House of Assembly, Abdulmalik Sarkindaji, announced a plan to marry off 100 orphaned girls. The solution to their vulnerability, it was decided, was to transfer them into the custody of men. Despite national outrage, the marriages went ahead. As if to prove this is now policy, the Zamfara State Government has, in 2025, arranged to sponsor the weddings of 200 more female orphans. It begs a sickening question: when will a world exist where older men are not obsessed with the bodies of girls young enough to be their daughters? According to Girls Not Brides, 30% of Nigerian girls are already married before 18. The state, rather than fighting this epidemic, is now its official matchmaker.

It is this same government that has failed so profoundly to provide security from rapists, kidnappers, and child-predators that is, ironically, obsessed with policing our uteruses. While millions of Nigerian women navigate a landscape of fear with no guarantee of justice or protection, the Nigerian Senate has been busy debating a bill to impose an increased 10-year jail term for abortion-related offences. In a breathtaking display of skewed priorities, the initial recommendation for punishing sexual assault was a mere five years.

Nigeria’s Government Strictly Polices Our Bodies

Our laws permit abortion only to save a woman’s life, leaving no legal recourse for victims of rape and incest. The consequence is a silent pandemic of desperation. The Guttmacher Institute estimates that hundreds of thousands of unsafe abortions occur annually in Nigeria, feeding a horrifyingly high maternal mortality rate. Denied safe and legal options, women are forced into the shadows, into the hands of unqualified practitioners in unsanitary conditions, often paying with their lives. The bill, now sent back to committee for a clearer definition of “unlawful abortion,” hangs over our heads—a legislative sword threatening to punish women for seeking autonomy over their own bodies, a right the state has already proven incapable of protecting from external violence.

To Be A Nigerian Woman Is To be Tired

To be a Nigerian woman today is to be exhausted. Exhausted from fighting kidnappers in our community and predatory relatives in our homes. Exhausted from screaming for justice that rarely comes. Exhausted from watching our leaders legislate control over our wombs while offering no protection for our lives. Exhausted from surviving, when all we want is the chance to simply live. This is, without hyperbole, a terrible time to be a Nigerian woman. The question is not just how long we can endure this, but when—and how—we will finally reclaim our right to exist in peace and with dignity.