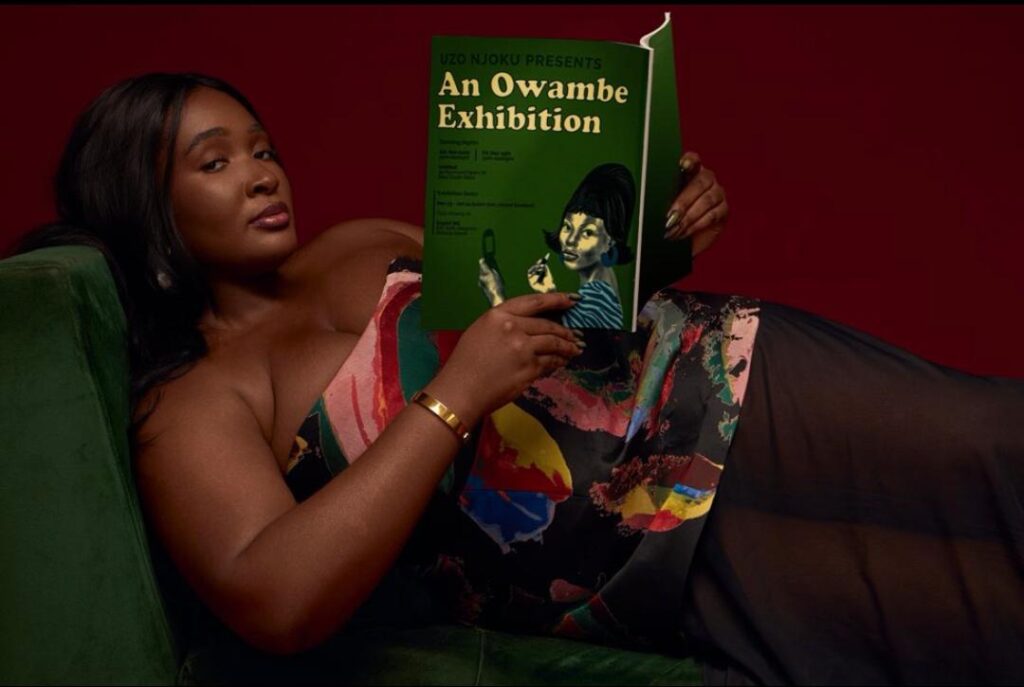

It takes a specific kind of audacity to trade a stable career path in statistics for the unpredictable world of fine art, especially when you are an immigrant daughter in the diaspora. But Uzo Njoku deals in audacity, carving a lane entirely her own as an “Artrepreneur.”From working night shifts caring for the elderly to funding her own path through art school, Njoku’s rise to prominence is a masterclass in grit.

Now, as her distinctive patterns and vibrant portraits command global attention, she faces a new challenge: public scrutiny from her buzzy on-going Owambe exhibition in Lagos. In this candid conversation, Njoku opens up about protecting her peace, knowing her worth, motherhood and the art of being a “shrewd businesswoman.

Hi, Uzo! Let’s Kick Things Off With 3 Words That Describe You Best.

The first word will definitely be self-motivated. I don’t know if my next word is a new word, but basically an “artrepreneur,” which is someone that is an artist and an entrepreneur. The last word is community-focused.

Ouu, those are powerful words. Now I am curious about your origin story as an artist. Can you take us back to the very beginning? What was the moment, or the series of moments, that made you realize art wasn’t just a skill, but a calling for you?

I think I basically realized that I needed to make it and also prove to my family that art is actually a career path. So I would say even from the very beginning of being restricted from participating fully in art, I knew that it was not something I could just treat as creating for creation’s sake. It had to be something that was feasible.

I went to school overseas in Virginia, and majority of the students in my school, are white students, you know? They were so relaxed. And it was actually because their parents already had them set up so they were literally just studying art for fun. It wasn’t like they planned a career in it. And that’s when I realized that no one’s gonna teach me how to make money out of art. It also didn’t help that the current pathway to being a successful artist at the time only let a small percentage of artists. I had to basically create my own pathway. So, I’m in school at Virginia, I’m top of the students, and no one else is really taking it seriously because they have no desire to continue long term, I knew that I had to figure out how to make my art a long-term thing for own myself.

It’s common knowledge that you were studying statistics and you were on track for a stable career that would have probably made your parents very happy. Knowing how Nigerian families are famously cautious of creative careers, how did you survive that initial period of switching majors with your family?

It was hard. I don’t think any regular person would have easily survived. I feel like it’s not an easy path for everyone to take, especially when your parents pull financial funding. It made things hard. I had to take on so many jobs just to be able to get through school. I was working at a grocery store and an art store at the same time. And then at nighttime, I was taking care of a 96-year-old woman just so I had a place to stay. Then I also had to make time for art—not just creating for class, but creating to understand what body of work I wanted to explore. Now, I realize how valuable my time was.

Woah. Cutting funding for your schooling? That’s insane. With how far you have come, I am sure your parents are more supportive of your art career.

Yeah.

It actually took a lot longer for my dad to kind of understand. I think it was when he came to my last New York exhibition that he got it. He understood how much I had achieved. We had a conversation in January, and he said the only thing he asks of me is to be a “shrewd businesswoman.” He basically advised that I be extremely shrewd with my decisions, how I spend my money relating to my business, and things like that. So for him to even sit down and talk to me at that capacity means that I’ve definitely gained his respect.

Your prints and patterns have become instantly recognizable. What goes into building that level of distinct visual identity?

The patterns are easy to recognize because, truthfully, there aren’t many Black pattern-makers outside of Africa. Even within Africa, the wax print makers are usually older generations who unfortunately don’t often own the copyright to their designs. So, I don’t have much competition in that specific lane, especially because I supplemented being self-taught with a lot of historical research. My knowledge base is layered.

When my contemporaries and I started out, we all looked up to Kehinde Wiley and Kerry James Marshall. The main draw with Kehinde Wiley was how he did portraiture behind patterns. But as I studied the work, I realized he wasn’t designing those patterns; he was painting against existing ones. I realized there were actually two people involved in the creation of that artwork—the painter and the pattern designer. I decided that to truly evolve, I needed to be the one doing both. I had to learn how to make my own patterns to own the full scope of the work.

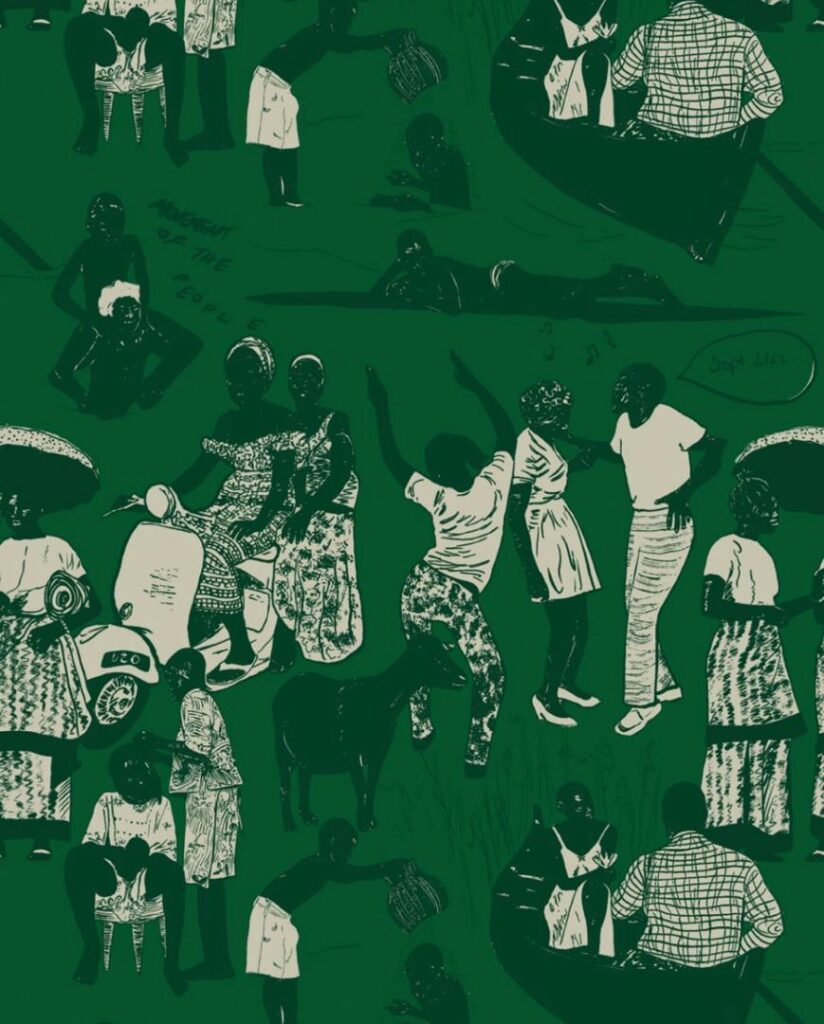

When it comes to the paintings themselves, I actually don’t stick to one specific style. I have my community pieces, which feature smaller cut-out shapes and distinct settings, and then I have my portraiture, which ranges from very flat to very detailed. The thread that connects everything is my color palette. I am very big on color theory. The colors I select are designed to capture the vibrancy of Black joy. That, coupled with the movement in the pieces, creates a specific feeling. When people see that “Black joy” aesthetic, they know it’s my work. Even if I put three different pieces together that aren’t the exact same style, they are unified by that vivid, distinct color story.

So, as a shrewd business woman, what part of the business side in being an artist surprised you the most?

The most surprising thing is realizing just how important it is to understand the background of whatever industry you’re in. For the art and music worlds to function at their current capacity, they often rely on exploitation. It shocked me to see how many people don’t understand that you need to carry yourself in a certain light. It is not just about being creative, you need to understand the logistics.

I found myself surrounded by peers who are creative with their hands, but they lack creativity when it comes to business innovation or protecting themselves. I’ve seen some crazy contracts and deals pitched to me. Because I run a business, I know the behind-the-scenes reality. I look at a deal and think, “Why would you even present this to me?” But I realize they do it because it works on other artists who simply don’t know better.

These artists don’t know that the price presented to them makes no sense. They don’t know that they should fight for their copyright or for exclusivity. Even when you look at a contract, you have to realize: They are coming to you because they need you. You have the right to fight for more or to demand that things be changed. A lot of people don’t do that. That has been my biggest takeaway: watching other artists enter contracts without knowing what is going on around them. I don’t blame them, some people just want to create and don’t want to deal with the business side of creating, so I can’t look down on them. But it has definitely been a shock to me.

As a creative myself, I can’t stand it when artists are exploited. What 5 business tips can you share with a creative reading this?

1. Diversify Your Circle

Don’t surround yourself with only like-minded people. If everyone in your circle is in the same industry, you’ll just have the same repetitive conversations and it takes you nowhere. You need a breadth of different people because you never know who knows who, or what additional knowledge someone from a different background can bring. Diversity is essential for personal growth.

2. Switch Your Medium

When things get hard creatively, look at another medium. You don’t have to stick to just one way of creating. If you are stuck in one area, pivot to another to keep the creativity flowing.

3. Don’t Box Yourself In

You don’t have to stick to one thing in life; you are allowed to evolve. If you start as an artist but decide you want to become an actor, do it. No one should be able to put you in a box, and you certainly shouldn’t put yourself in one. Keep your mind open to growth, critique, and the evolution of who you are.

4. Save for a Rainy Day

Save. And then save more. Just because you receive a large lump sum of money doesn’t mean you should buy what you want immediately. Save towards your desires, but always keep a safety net. I still put money aside for a rainy day because, inevitably, it will come in handy.

5. Create and Host Community

Create community. We are becoming so individualistic, but it is vital to host friends and invite people into your home. It doesn’t always have to be about going out to restaurants. Connect with people. This is especially important for women, because as we start families, life can get lonely. Your community might change as you progress—the friends you have now might not be the friends you have in five years—but you must always hold onto and support a community.

Looking at your journey so far, from America to Nigeria and around the world, how would you describe the phase you are currently?

I would describe this as a transitional phase. Leading up to my last exhibition in New York, I was trying to figure out my purpose. I had reached a point where I felt like I had achieved all my initial goals, and honestly, I was kind of bored. I found myself sitting at home asking, “What do I do now?”

But now, I feel like I’ve figured that out. I am simply making new goals and achieving them. I know that after this Owambe show, I have a show in London, and then I plan on taking a two-year hiatus to start a family. I’ve heard that motherhood is not an easy adjustment, so I wanted to hit these two major milestones—Lagos and London—before I say, “Okay, pause. Let me calm down a bit and see what this new chapter of motherhood looks like and how it fits into my art.”

I wish you the happiest home and the happiest, healthiest baby when you do decide to start your journey.

Thank you

This leads me to ask, as someone whose work centers Black joy and African heritage, how has your own understanding of joy, identity, and womanhood evolved over the years?

I’ve come to realize there isn’t a blanket idea of what womanhood is; it differs for every person. Over the years, through painting and meeting so many people, I have definitely become more patient. I listen a lot more now. Many people listen just to respond, but I listen to understand. I’ve realized that people’s backgrounds shape who they are, so I try not to form opinions too quickly.

As for my work, especially as an artist who travels a lot, my focus is capturing the threads that tie the diaspora together. I might create something focused on West Africa, but a Caribbean viewer will resonate with it, or an African American will see the American South in the imagery. It’s beautiful to see that connection. I am creating a world where people can come in and find respite. I’m just happy to provide those little pockets of joy, whether through a canvas or a product in their home, despite whatever else they might be going through in life.

Talking about joy and identity, congratulations! It’s been one week since the Owambe exhibition opened in Nigeria. And it’s been one of the most talked-about events in the art scene this year. What inspired it and how do you feel bringing such a culturally rich body of work back home for Nigerians to experience?

I’ve noticed that usually, the people who tend to get the art scene here are either Lagosians or those living abroad. I wanted to bridge that gap and create something that a lot of people would be interested in. With this body of work, I focused on fabrics, products, and conversational pieces to meet the Nigerian audience at a middle point.

I didn’t want the exhibition to be just another white space where you walk in, take a picture, and leave. I wanted it to be homely, with programming that truly engages people. When people come in, they smile; they leave happy and tell their friends. So, despite the noise, negative drawbacks and the attempts to put the project down, I am happy. There have been so many positive takeaways, and this is just the start. We keep going.

You mentioned “the noise,” and that leads us directly to the elephant in the room. Owambe didn’t just invite viewers in; it sparked a massive debate on cultural ownership, specifically surrounding the use of Yoruba aesthetics by an Igbo artist. How have you navigated that storm personally? Did the backlash make you want to retreat, or did it only reinforce your resolve?

I believe criticism should be honest feedback, but I felt this criticism wasn’t honest, especially after how many times I kept explaining myself. In fact, my biggest mistake was trying to explain myself. Especially when I was speaking with the commissioner, she asked me the same questions many of these people were asking: “Did you print Igbo words on Adire?” and I had to keep clarifying: “I made Ankara. It was produced at Sunflag, and they only make Ankara.” Yet, people insisted on their own narrative.

People want to misconstrue what I say: they say that I have never said that Owambe is a Yoruba word. Well, yes I did, even from two years ago, I stated that Owambe is a Yoruba word and that Lagos is Yoruba land. If the majority of the people I am collaborating with are Yoruba, it is because I am in Yoruba land. Does that make the show about Yoruba Heritage? No. Are the people involved because I’m in Yoruba land? Well, If you reach out to me to work, I’m gonna give you an opportunity because I have a platform.

I also get backlash from people in the East asking, “Why don’t you come home to the East?” My answer is simple: I don’t make decisions based on emotional sentiments; I make them from a business point of view. Lagos is the hub. It is where the diaspora, my core audience, returns. It is the new market, I am focusing on. Even Abuja is big, but business-wise, Lagos makes more sense.

I just feel like the people talking are not in my shoes. They have never been in my shoes. They are never going to be in my shoes. The artists who did stand up for me are the ones who understand the business and realized the criticism made no sense.

If you give me money to do something for the culture, that’s a whole different ballgame. We can get it done. But Owambe is a solo exhibition. It is my solo exhibition. So why are you trying to tell me about my exhibition that I planned with my money? It’s just so funny. Ultimately, I think it boils down to this: People do not like successful, proud, opinionated women whose success they cannot trace to a man. It makes them uncomfortable.

But at the end of the day, my reality is not tied to social media. I can turn off my phone and still bring my vision to fruition. All that backlash was just noise. It didn’t stop the show. I was just shocked to see people fight so hard over nothing; imagine if we put that energy toward something useful?

Can you share how you protected your peace and blocked out the noise?

I just worked. I just had to keep working. When I had to block out the noise, I used mute button. The only time anything came to my attention was if someone close to me sent it. Otherwise, once you say some nonsense, I mute you. I don’t block, blocking doesn’t work for me. I prefer to mute. You can be spazzing under my comments, saying the most horrible things, and I won’t see it. It doesn’t reach me.

Pricing is the number one anxiety for many emerging Nigerian artists. You went from selling affordable prints to commanding serious prices for your originals. What is your formula or philosophy to pricing?

When it comes to my original paintings, I establish a baseline for pricing by visiting a gallery first. This gives me a clear understanding of the market, what collectors are willing to pay and at what price point. I also treat commissions differently; they command a higher price because you are paying for the specificity of your vision.

The beauty of my business model is that it is diversified. I am not just painting, I run an art store, I handle brand commissions, and I sell originals. While the value of my original paintings rises, I make a conscious effort to keep my product pricing accessible. I never want to lose that entry point for people who want to own a piece of my brand but aren’t ready for a canvas.

My philosophy on pricing is simple: account for your time, account for your materials, but most importantly, account for your future. When people buy art, they are investing in the artist. If you want to command high prices, you have to be locked in. It’s either you go through galleries and they’re pricing you up or you are independent and demanding the price that you want. If you are active and dedicated you will get the price you demand because people are excited for your future and betting on it.

If you could go back in time to younger Uzo sitting at her Statistics class feeling out of place and ready to switch to art, what would you tell her?

Save every penny. Seriously, save every little bit of money you can. It would have made a huge difference. There is a strange psychological shift when you go from having nothing to suddenly landing a large sum of money from art. You just don’t believe you earned it, you know? Because art pricing isn’t always linear. It’s like “oh, I painted this for an hour” and now I am selling it for a lot. You get a lot of disconnection from the pricing. You receive this money and think, “I don’t deserve this. I didn’t earn it.”

So, I would tell little Uzo: Save your money, but also, stop the Imposter Syndrome. You deserve everything you have received. You earned it.